Ignatian spirituality is one of the most influential and pervasive spiritual outlooks of our age. There’s a story behind it. And it has many attributes.

1. It begins with a wounded soldier daydreaming on his sickbed.

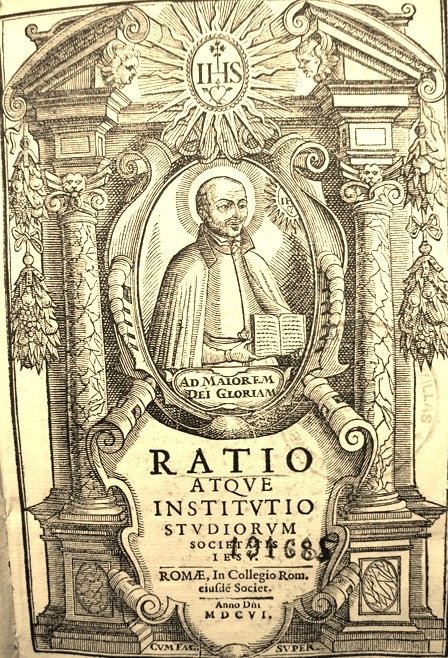

Ignatian spirituality is rooted in the experiences of Ignatius Loyola (1491–1556), a Basque aristocrat whose conversion to a fervent Christian faith began while he was recovering from war wounds. Ignatius, who founded the Jesuits, gained many insights into the spiritual life in the course of a decades long spiritual journey during which he became expert at helping others deepen their relationship with God. Its basis in personal experience makes Ignatian spirituality an intensely practical spirituality, well suited to laymen and laywomen living active lives in the world.

More about Ignatius Loyola (A)

2. “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.”

This line from a poem by the Jesuit Gerard Manley Hopkins captures a central theme of Ignatian spirituality: its insistence that God is at work everywhere—in work, relationships, culture, the arts, the intellectual life, creation itself. As Ignatius put it, all the things in the world are presented to us “so that we can know God more easily and make a return of love more readily.” Ignatian spirituality places great emphasis on discerning God’s presence in the everyday activities of ordinary life. It sees God as an active God, always at work, inviting us to an ever-deeper walk.

3. It’s about call and response—like the music of a gospel choir.

An Ignatian spiritual life focuses on God at work now. It fosters an active attentiveness to God joined with a prompt responsiveness to God. God calls; we respond. This call-response rhythm of the inner life makes discernment and decision making especially important. Ignatius’s rules for discernment and his astute approach to decision making are well-regarded for their psychological and spiritual wisdom.

More about Call and Response (B)

4. “The heart has its reasons of which the mind knows nothing.”

Ignatius Loyola’s conversion occurred as he became able to interpret the spiritual meaning of his emotional life. The spirituality he developed places great emphasis on the affective life: the use of imagination in prayer, discernment and interpretation of feelings, cultivation of great desires, and generous service. Ignatian spiritual renewal focuses more on the heart than the intellect. It holds that our choices and decisions are often beyond the merely rational or reasonable. Its goal is an eager, generous, wholehearted offer of oneself to God and to his work.

More about the Spirituality of the Heart ©

5. Free at last.

Ignatian spirituality emphasizes interior freedom. To choose rightly, we should strive to be free of personal preferences, superfluous attachments, and preformed opinions. Ignatius counseled radical detachment: “We should not fix our desires on health or sickness, wealth or poverty, success or failure, a long life or a short one.” Our one goal is the freedom to make a wholehearted choice to follow God.

6. “Sum up at night what thou hast done by day.”

The Ignatian mind-set is strongly inclined to reflection and self-scrutiny. The distinctive Ignatian prayer is the Daily Examen, a review of the day’s activities with an eye toward detecting and responding to the presence of God. Three challenging, reflective questions lie at the heart of the Spiritual Exercises, the book Ignatius wrote, to help others deepen their spiritual lives: “What have I done for Christ? What am I doing for Christ? What ought I to do for Christ?”

More about the Daily Examen (D)

7. A practical spirituality.

Ignatian spirituality is adaptable. It is an outlook, not a program; a set of attitudes and insights, not rules or a scheme. Ignatius’s first advice to spiritual directors was to adapt the Spiritual Exercises to the needs of the person entering the retreat. At the heart of Ignatian spirituality is a profound humanism. It respects people’s lived experience and honors the vast diversity of God’s work in the world. The Latin phrase cura personalis is often heard in Ignatian circles. It means “care of the person”—attention to people’s individual needs and respect for their unique circumstances and concerns

.8. Don’t do it alone.

Ignatian spirituality places great value on collaboration and teamwork. Ignatian spirituality sees the link between God and man as a relationship—a bond of friendship that develops over time as a human relationship does. Collaboration is built into the very structure of the Spiritual Exercises; they are almost always guided by a spiritual director who helps the retreatant interpret the spiritual content of the retreat experience. Similarly, mission and service in the Ignatian mode is seen not as an individualistic enterprise, but as work done in collaboration with Christ and others.

More about Collaboration (E)

9. “Contemplatives in action.”

Those formed by Ignatian spirituality are often called “contemplatives in action.” They are reflective people with a rich inner life who are deeply engaged in God’s work in the world. They unite themselves with God by joining God’s active labor to save and heal the world. It’s an active spiritual attitude—a way for everyone to seek and find God in their workplaces, homes, families, and communities.

10. “Men and women for others.”

The early Jesuits often described their work as simply “helping souls.” The great Jesuit leader Pedro Arrupe updated this idea in the twentieth century by calling those formed in Ignatian spirituality “men and women for others.” Both phrases express a deep commitment to social justice and a radical giving of oneself to others. The heart of this service is the radical generosity that Ignatius asked for in his most famous prayer:

Lord, teach me to be generous.

Teach me to serve you as you deserve;

to give and not to count the cost,

to fight and not to heed the wounds,

to toil and not to seek for rest,

to labor and not to ask for reward,

save that of knowing that I do your will.